The Fine Art of Aging

Through another’s eyes

I hadn’t seen my cousin Hilda in over 30 years and was surprised to discover that at 91, she was still in the same suburban house where she has lived since the 1950s. On her own. Without a companion or housekeeper.

Her blond hair is white now. Her gait, a little unsteady. But I had no trouble recognizing the pretty, petite woman who had been the exception among the women of my parents’ generation. They identified themselves as “homemakers.” Hilda was an artist.

When she first took up painting in the 1950s, no one in the family took her seriously. She was an abstract expressionist at a time when painting-by-numbers and realism were popular. “Better she should learn how to cook for her husband than make like Picasso,” they said. To her credit, Hilda never turned on the stove. And she never stopped painting.

“Excuse the mess,” she said, leading me into her studio. It didn’t look messy to me. It looked glorious, filled with canvases, paints, paper, brushes. The tools of an artist still actively engaged in her work. Every room of her home was filled with her paintings, drawings and etchings. On the walls, piled on tables, leaning one against the other.

I could think of only one place that created this overwhelming assault on the senses. The Barnes Foundation. According to the founder’s eccentric methodology, every inch of wall space, from floor to ceiling, was filled with paintings and decorative art – without titles, names or dates.

I took a shot. “Hilda, have you been to the new Barnes?”

“No,” she said.

When Alfred Barnes assembled the largest collection of French impressionist art on his private estate outside Philadelphia in 1922, he made it almost impossible for the public to see it. It was like getting into the White House. No walk-ins. You had to make a request in writing and hope you were granted permission. In his will, Barnes made sure that his collection would never be moved.

However, in 2012, the executors of his estate broke the will and moved the entire collection into a modern museum in the city, in walking distance from the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Traditionalists, including my cousin, were furious. Which probably accounted for Hilda’s not stepping inside the new Barnes in the four years since it had opened. And yet she gladly accepted my invitation.

HILDA’S PERSPECTIVE

“I don’t like it,” Hilda snapped before even opening the museum’s door. “The architecture is too cold. The paintings aren’t happy here.”

Once inside, she was delighted to renew her acquaintance with works of art she hadn’t seen in decades. Sitting enthralled in front of Matisse’s “The Riffian,” a large painting of a Moroccan tribesman, Hilda said, “This has always been one of my favorites. But I’m seeing things I never noticed before, like all those green verticals.”

When her audio headset inexplicably jumped from English to Spanish, Hilda refused to get a new one. “I don’t need it,” she said and struck up an impromptu conversation with a stranger, a professional artist half her age. They talked shop, comparing the mediums in which they work and their subject matter. Hilda appeared to be enlivened by this chance meeting with a fellow artist.

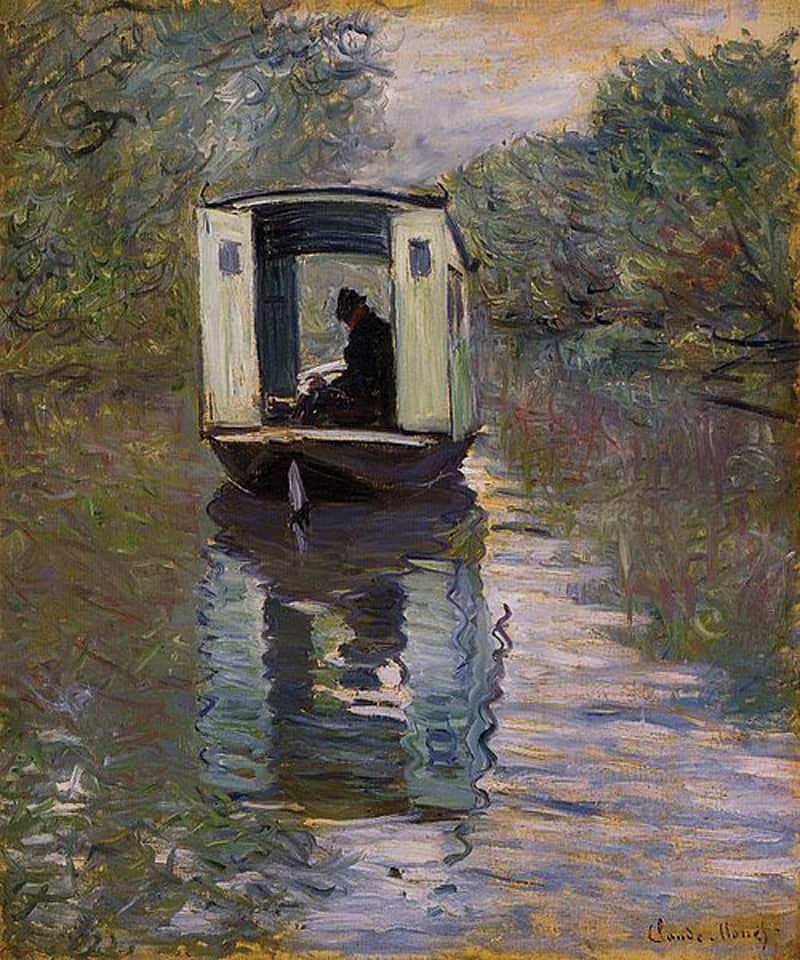

In one of the galleries, Hilda looked around the room anxiously. “There’s supposed to be a painting of a canal in that corner,” she said. The new Barnes was commissioned to replicate the galleries exactly as they had been organized at their former location; however, Hilda sensed something was wrong. Two galleries later, she sighed, “There it is!” The missing painting was Monet’s “Houseboat.”

“Look at how he painted the reflection in the water,” she said, “as if the boat is actually traveling away from you.” I had seen the famous painting innumerable times, but now, through Hilda’s eyes, I saw the boat move.

We took a break for lunch and never got to the second-floor galleries. Instead, we talked about Hilda’s life as an artist over gazpacho and avocado sandwiches at a nearby eatery.

I learned that my cousin had started painting in 1954, studying at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “My instructor didn’t put up with any nonsense,” said Hilda. “If you were there for therapy, he’d kick you right out.”

LESSONS LEARNED

Hilda continued to study at the museum for more than a decade. Like many members of the Philadelphia art establishment, her instructor did not subscribe to Barnes’ formulaic “philosophy” based on the writings of John Dewey. He discouraged Hilda from attending Barnes’ two-year program. Hilda, ever the independent, free-thinking rebel, applied anyway in the 1960s.

She recalled her nervousness at being interviewed at the home of the imperious Violette De Mazia, director of the Barnes Educational Program. “Her house was filled with masterpieces,” said Hilda. “She was rumored to be one of Barnes’ mistresses.” (When De Mazia’s art collection was auctioned at Christie’s in 1989, it brought in over $8 million.)

“They had very strict rules. You could not miss a session and had to do all of the assignments and readings,” said Hilda. “It was amazing.” She explained that the course gave her intimate access to masterpieces that, at the time, were not available to the public.

I hadn’t known that my cousin had taught children’s art classes at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Or that she was among the first to experiment with etching on steel and that her etchings are part of the collection at the University of Pennsylvania’s Shea Eye Institute. I also learned that Hilda has, like most people her age, serious health challenges, but, unlike her peers, she doesn’t dwell on the subject.

She prefers talking about art. The rewards of the creative life. The joy she takes in her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In doing so, my cousin gave me a glimpse into a future I hadn’t imagined. The knowledge that growing older doesn’t have to be about shutting down and loss. Aging can be a fine art if, like Hilda, you approach each day as a blank canvas with infinite possibilities.

Stacia Friedman is a freelance writer and author of Tender Is the Brisket. This article first appeared in Women’s Voices for Change, WomensVoicesForChange.org.