Has Baseball's Sparkling Diamond Lost Its Luster?

Changes nationally and in Richmond over the years – and into the future

Take me out to the ball game,

Take me out with the crowd.

Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack,

I don’t care if I never get back.

Let me root, root, root for the home team.

If they don’t win, it’s a shame

For it’s one, two, three strikes, you’re out

At the old ball game.

What other sport has its own song, known around the world? What other sport allows time to grab a hot dog and beer or take in entertainment during multiple game breaks? But what used to be considered “America’s pastime” is struggling to remain relevant among today’s many sport choices.

Entertainment and expanded food options (think sushi and pork belly mac and cheese) will play a starring role in its comeback, particularly in the minor leagues, as with our own Richmond Flying Squirrels, members of the Eastern League and Double-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants. “Welcome to Funnville,” the team proclaims.

“Squirrels’ games are so much fun, one ‘n’ simply isn’t enough,” says Todd “Parney” Parnell, vice president and COO.

One glance at the between-innings wackiness will assure you of how much fun a game can produce: “racing nuts,” folks in a horse costume, games of horseshoes involving toilet lids and plungers – and Parney flopping around the outfield trying to catch T-shirts shot out of a cannon.

KEEPING FANS ENGAGED

Such is life in the minor leagues. Ah, but the majors have made some changes over the years to keep fans interested, too.

One of the biggest early on was the transition from the so-called “dead ball” era (from 1900 to 1919) to a livelier ball and smaller stadiums, resulting in an explosion of home runs, making it more exciting for the fans.

This turnabout was led by Babe Ruth, who singlehandedly changed the face of baseball. In 1918 for the Boston Red Sox, Ruth tied for the league lead with 11 homers. The next season, Ruth slugged 29, setting an American League record.

Then, in 1920, after being sold to the New York Yankees, Ruth clubbed 54 and continued to break his own records until he smashed 60 in 1927. The Babe wound up with 714 homers to help the Yankees begin their domination of the American League.

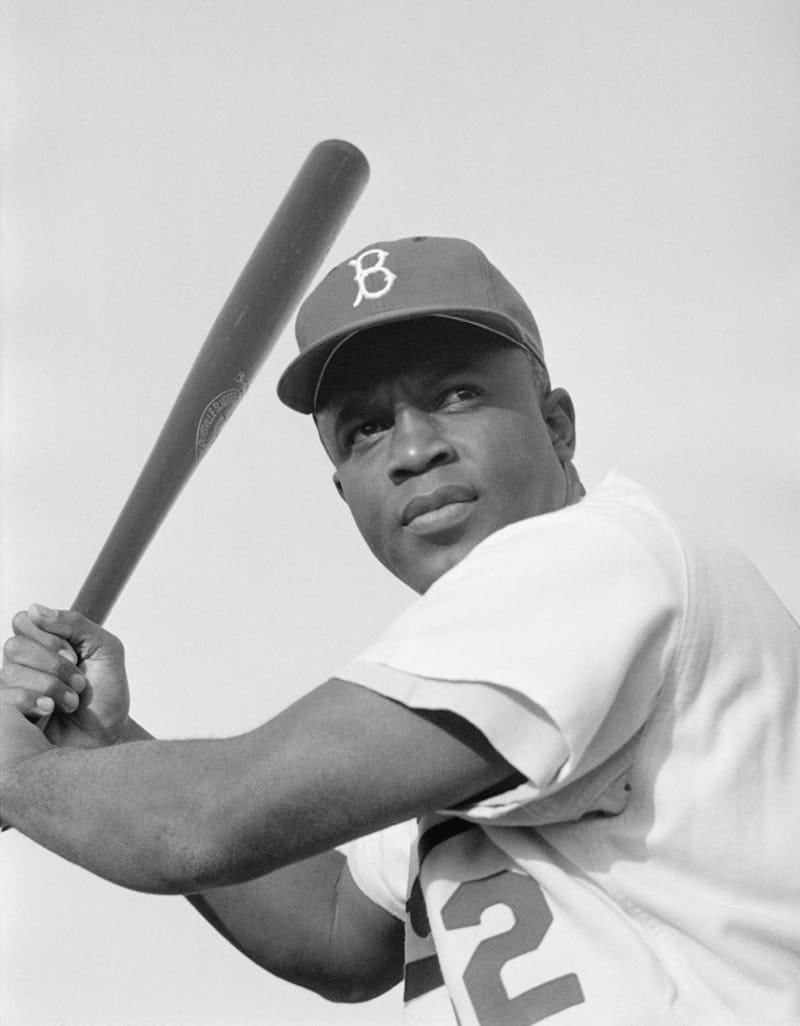

The next big change came when Jackie Robinson became the first African-American major leaguer. He took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, paving the way for others like Larry Doby, Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, Ernie Banks, Satchel Paige and Hank Aaron.

Breaking the color barrier took tremendous courage in those segregated days, not only from Robinson but from the baseball executive who signed him, Branch Rickey, general manager of the Dodgers. Rickey called it an “experiment,” but he felt it was the right time to integrate the major leagues.

“I want a ballplayer with the guts not to fight back,” Rickey told Robinson as they prepared to cross the color line. Rickey knew that Robinson would have to overcome all manner of ugly comments from the stands and on the field.

Robinson survived taunting from fans and players, spikings and even threats on his life to become a major contributor to six National League pennants for Brooklyn in 10 years.

Major League Baseball announced in January that it will dedicate the 2019 season to the 100th anniversary of Robinson’s birth, commemorating it with ceremonies and youth initiatives in support of the Jackie Robinson Foundation.

PLAYING HARDBALL IN RICHMOND

While the major leagues continued to enjoy popularity, in part because of the advent of night games, television and the addition of a designated hitter in the American League in 1973, Richmond was carving out its own niche in the baseball world.

The sport was introduced to Richmond in 1866, shortly after the Civil War had ended. The first professional attempt came in 1884, when the Virginians became charter members of the Eastern League and played at the Virginia Baseball Park, at the west end of Franklin Street, where the Robert E. Lee statue would later be erected.

Later that season, Richmond joined the American Association, one of the two original major leagues. That would last only half a season, however, and after one more season in the Eastern League, Richmond had no team from 1886 to 1894, according to W. Harrison Daniel and Scott P. Mayer in Baseball and Richmond: A History of the Professional Game, 1884-2000.

Richmond’s team became known as the Colts in the early 1900s, playing home games on Mayo Island, eventually winding up in the Piedmont League.

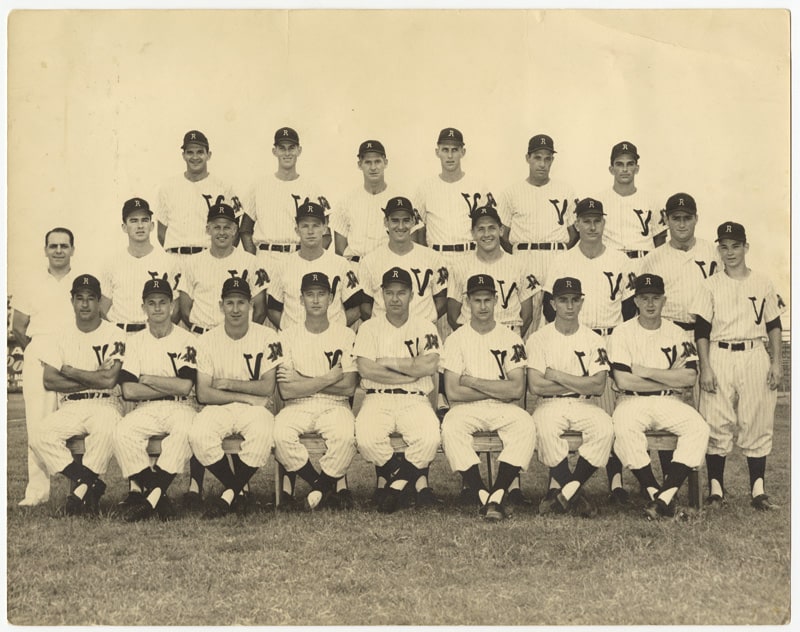

After 21 years in the Piedmont League without any major-league affiliation, Richmond became a member of the International League in 1954. The Virginians played at renovated Parker Field on the Boulevard. In 1956, the Vees, as they were known, entered into an agreement with the Yankees, which lasted until 1964.

One year later, the Atlanta Braves took over the franchise. The R-Braves entertained fans until 2008, when Atlanta moved the team to Georgia. During their tenure, in 1984-85, Parker Field was transformed into The Diamond.

After no baseball in 2009, those acrobatic Flying Squirrels moved into The Diamond in 2010. During the past decade, the Squirrels have become entrenched in the Richmond sports scene.

“I think the one word is ‘community,’” says Parnell. “We have worked diligently over time to be much more than just a minor-league baseball team. We wanted to become an integral fabric of the community. We work year-round to do that. One of my favorite sayings when I’m speaking is ‘We loved Richmond and Richmond loved us back.’”

During Squirrels games, there is rarely a moment when something isn’t going on, from the action on the field and craziness between innings to fireworks after many weekend games.

“You have to have something for everybody,” says Parnell. “Dad may like the baseball. Mom might like funnel cakes. The son might like running around the ballpark and interacting with other kids at the game and the daughter might like seeing [mascots] Nutzy or Nutasha.

“Or getting autographs from the players or catching a foul ball. There’s so many elements involved in the fan experience. Our whole attitude from day one was we’re not in the baseball business, we’re not in the entertainment business, we’re in the memory-making business.”

This season, the Squirrels debut a new video board and host the 2019 All-Star Week festivities in July, featuring Country Music Jam concert, celebrity home-run derby and the All-Star game.

Parnell and the rest of the Squirrels’ front office is hoping the future will bring a new stadium to replace the aging Diamond.

CHANGES FURTHER AFIELD

Baseball is unique in many ways, not the least of which there is no time limit. That means games don’t end until one team scores more runs than the other. And sometimes, an extra inning or two – or more – is needed, i.e., “free baseball.”

It also means that games can last three or four hours, and that upsets the casual fan.

Major League Baseball is planning changes, some as soon as this season. In an effort to speed up the game – and keep people awake until the end – administrators are planning to install a 20-second maximum between pitches.

Last season, the number of visits to the mound by catchers and pitching coaches was limited to six. In addition, relievers will have to pitch to a minimum of three batters, which would keep managers from changing pitchers for matchup purposes and slowing the game down.

Although there is still fierce opposition to it, the designated hitter appears destined to be used in the National League in the next few years. Putting a runner on second base to start the 10th inning is another possibility.

To remain part of the fabric of our society, the game of baseball must make some changes to pick up the pace.

NATIONAL BASEBALL STARS IN RICHMOND

According to Baseball and Richmond: A History of the Professional Game, 1884-2000, one of the biggest occasions involving pro baseball in Richmond came on Oct. 10, 1911, when major-league all-stars – including Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker and Walter Johnson – played Manager Connie Mack’s World Series-bound Philadelphia Athletics before a crowd of 9,000 at Broad Street Park.

The mighty Babe made two appearances in Richmond, as mentioned in the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

The first came in 1922 when he was coming off one of the best seasons of his storied career with the New York Yankees. In the exhibition against the Brooklyn Dodgers, Ruth blasted a homer that is considered the longest in the history of the Mayo Island ballpark, according to the Times-Dispatch account.

Twelve years later, the Babe was in town for an exhibition against the minor-league Richmond Colts. In batting practice, Ruth smashed three balls out of Tate Field on Mayo Island, including one that splashed into the nearby James River. In his only at-bat, Ruth popped up.

Ray Dandridge became Richmond’s only native member of the baseball Hall of Fame, inducted in 1987.

Born in Church Hill, Dandridge attended George Mason Elementary. At 19, he signed with the Detroit Stars of the Negro National League. He became a star third baseman. A contact hitter, he never got the attention that Negro League stars like Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell received.

Nevertheless, the Richmonder was a star in the Negro Leagues, as well as leagues in Cuba, Mexico, Puerto Rico and Venezuela.

In 1949, Dandridge batted .362 for the farm team of the NL’s New York Giants. The next year, he hit .311 with 80 RBI and was named MVP for the Triple-A Minneapolis Millers. Despite his success, he was never promoted to the majors, mostly because the major leagues were still not adding many African-Americans to their rosters in segregated America.

“Dandridge didn’t get the chance to play in the majors,” said fellow Hall of Famer Monte Irvin. “But he had major-league talent. He was a superstar.”

John Packett is a former sports writer for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, where he covered nearly every sport from high schools to the pros during almost 40 years. He retired in 2009 and spends his time writing freelance articles and doting on his grandson, Kylan.