‘Pentimento Memories of Mom and Me’

Preface from ‘The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise’ by Robert W. Norris

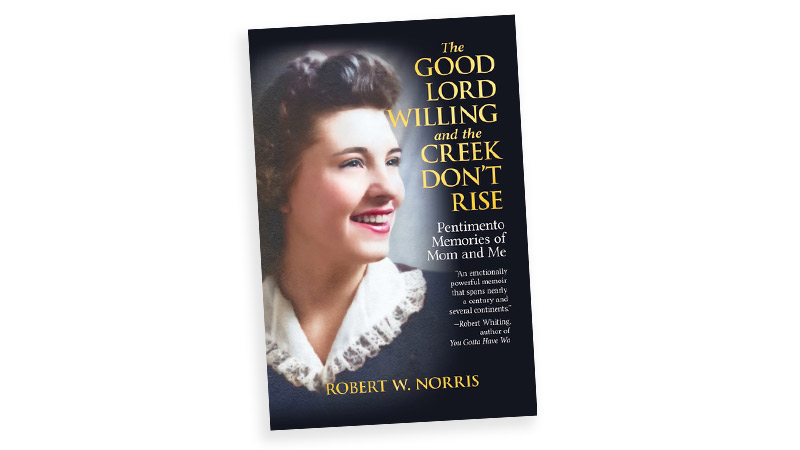

After his mother died in January 2021, Baby boomer Robert W. Norris wrote and published her obituary. It was well received by family and friends, but he wondered, “Could Mom’s life, her vitality, her entire essence be reduced to four paragraphs of dry, dreary prose?” He decided not and wrote a book combining his life story and a tribute to his mom, entitled The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise: Pentimento Memories of Mom and Me. This preface from his book (used with permission) provides a taste of Norris’s celebration of his mother’s life.

Preface

On January 11, 2021, my seventieth birthday, Mom fell into a coma. Three days later and four days short of her ninety-fifth birthday, she died peacefully. My sister Terri was at her side. I felt a deep emptiness and loneliness that still lingers. I was once again a lost little boy who couldn’t find his mama to run to for warmth and comfort.

Terri and a close cousin asked me to write the obituary. I had to keep it fairly short as newspapers now charge for the service. Here’s how it turned out.

Catherine Caroline (Murphy) Schlinkman

Catherine Caroline (Murphy) Schlinkman, 94, passed away at her home in King City, Oregon on January 14, 2021. Kay, as she was known to all, was born in Grand Forks, North Dakota to Lorna (Frederick) Murphy and Patrick Murphy on January 18, 1926.

Kay grew up in White Salmon, Washington, where she attended Columbia High School and was active as a cheerleader and majorette in the marching band. After graduating high school, she attended a business school for two years in Portland, Oregon, then married Bill Norris in 1946 and moved to Humboldt County, California.

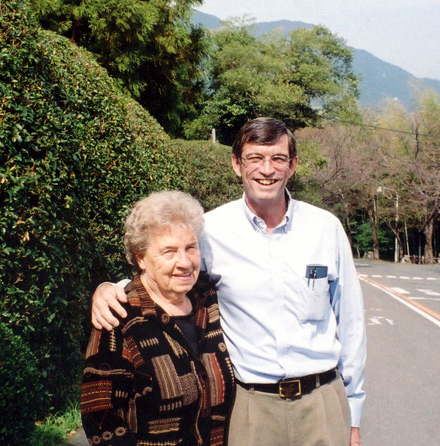

Kay had a full and active life. She enjoyed music, painting, golf, writing, traveling, and dancing. For a time in the 1950s, she became a roller skating instructor. In the 1960s and 1970s, she learned to fly, got a private pilot’s license, worked at the Truckee Tahoe Airport, and flew fire patrol for the Division of Forestry for two summers. She spent most of her working career as a legal secretary. Her travels took her to Japan seven times and once to Ireland in 2003 to trace her father’s family roots on a three-week journey with her son Robert and his wife Shizuyo. Her warmth and good cheer made her many friends from around the world. Beginning in her 60s, she began studying the Japanese language and continued into her 90s.

Kay is survived by her three children: Richard C. Norris, Robert W. Norris, and Terri M. Norris.

Everyone was pleased with it. A local newspaper ran the obit with a wonderful picture from Mom’s high school days. I felt empty. Could Mom’s life, her vitality, her entire essence be reduced to four paragraphs of dry, dreary prose? Was that how people would remember her?

She was so much more than that. In many ways, Mom’s is the story of a remarkable American woman, a fighter, and a survivor of the time in which she lived. As a child, her experience of traveling across the United States with her family in the early days of the Great Depression was not unlike that of the Joad family in Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Being ostracized by a small logging community in the late 1950s for her divorce and later being kicked out of the Catholic Church when she remarried were symbolic experiences. When I became a conscientious objector, refused my order to fight in the Vietnam War, got court-martialed, and spent time in a military prison, Mom bravely defended me against patriotic and conservative friends, colleagues, neighbors, and family members who considered me a coward and a traitor. This courage also exemplified her life.

At heart, she was a feminist ahead of her time who fought against sexual and power harassment in the home and workplace. After her second divorce, in addition to her main day job as a legal secretary, she took on two hourly-wage jobs – one wrapping presents at a mall and one splitting time between night clerking and cleaning rooms at a hotel – in order to pay off thousands of dollars in gambling debts her second husband left behind. She didn’t have money for gas, so she bicycled to work in the snow. In her forties, when she was a licensed pilot flying for the Department of Forestry as a forest fire spotter, she became chairperson of the Reno chapter of Ninety-Nines, the women pilots’ organization whose first president was Amelia Earhart. Later, she took night classes to qualify as a legal secretary, worked at three law firms in that capacity, and finally retired at seventy-eight. In the end, she’d gained a hard-earned independence and a pension to pay for living expenses for herself and Terri, who could not work because of disability caused by multiple sclerosis.

Mom was an artistic soul who painted oil and sumie scenes of animals and nature, wrote haiku poems, and played the piano for social gatherings. She played the Catholic church organ for seven years of Sunday sermons before her priest refused to administer Communion one Sunday after her divorce. When he bypassed her at the Communion rail, she grabbed him and gave him a piece of her mind in front of the whole congregation.

She was an adventurer who traveled to Japan, Ireland, Costa Rica, and Canada. She made friends with people in all those countries and kept up a lifelong correspondence with many of them. She was an athlete who, in addition to her high school cheerleading and majorette activities, played golf, umpired Little League games, bowled in a city league, water-skied, roller-skated, practiced aerobics, and did a lot of mountain trekking. In short, she was a ball of energy.

Her hug was the strongest and best in the world. Her love was true, and you knew she meant it when she hugged you. The last time I got one of those hugs was in August 2015 when I chaperoned some Japanese university students to a Portland, Oregon homestay-study program that I’d arranged through the Japanese university where I taught. I treasure the memories of those times with Mom and Terri.

Her hug was the strongest and best in the world. Her love was true, and you knew she meant it when she hugged you. The last time I got one of those hugs was in August 2015 when I chaperoned some Japanese university students to a Portland, Oregon homestay-study program that I’d arranged through the Japanese university where I taught. I treasure the memories of those times with Mom and Terri.

Memories, however, fade quickly. After Mom’s death, I was left with a lot of pictures, copies of our e-mail correspondence dating back to 1998, dozens of actual letters dating back to the late 1980s, a couple of videos of Mom, and about five hours of audio files I recorded of stories Mom told during a 2010 trip I took to Portland. I have a multitude of images in my head from childhood, adolescence, hippie ramblings, the times she visited Japan, our journey to Ireland, and much more, but these images are forever changing.

I’ve always been interested in Lillian Hellman’s usage of the word “pentimento.” In the introduction to Pentimento: A Book of Portraits, Hellman wrote:

Old paint on canvas, as it ages, sometimes becomes transparent. When that happens it is possible, in some pictures, to see the original lines: a tree will show through a woman’s dress, a child makes way for a dog, a large boat is no longer on an open sea. That is called pentimento because the painter “repented,” changed his mind. Perhaps it would be as well to say that the old conception, replaced by a later choice, is a way of seeing and then seeing again.

Don’t we all handle our memories that way? In the end, do our memories preserve the truth, or do they hide it? Or is the truth always changing? Did all those things in the past really happen? Were they merely dreams, figments of the imagination? Timothy Dow Adams in Telling Lies in Modern American Autobiography wrote that for Hellman, “pentimento becomes a metaphor for memory, an analogy to the particular difficulty of artistically remembering a life, telling the truth despite the mendacity of memory.”

What I do know is that the feelings these memories evoke are entirely real. I want to preserve them. This book is a pentimento journey into the memories that came to me while going through Mom’s letters and tapes – and a journey into the memories of my own life. It’s a telling of a decades-long conversation I have constantly in my head: the two of us sitting at Mom’s dining room table, sipping cups of coffee, and discussing our lives and experiences.

During the last month of Mom’s life, she often fretted about her loved ones forgetting her. “Please don’t forget me,” she implored Terri and me several times. It was hard to convince her that we wouldn’t. If Mom is up there in heaven and still worried about that, here’s what I’d like to say to her: Mom, no one who ever met you could possibly forget you. Believe me, we’ll always remember, love, and cherish you. We’ll always remember your infectious laugh, your warmhearted hug, and your family stories. Oh, those stories. That’s why I wrote this book!

Robert W. Norris was born and raised in Humboldt County, California. He was a conscien-tious objector to the Vietnam War and served time in a military prison for refusing his order to fight. In his twenties, he roamed across the United States, went to Europe twice, and made one journey around the world. In 1983, he landed in Japan, where he became a professor at a private university and retired as a professor emeritus. He is the author of three novels, a novella, a memoir, and over twenty research papers on teaching. He and his wife live near Fukuoka, Japan. Click here to find out more about Norris.

Robert W. Norris was born and raised in Humboldt County, California. He was a conscien-tious objector to the Vietnam War and served time in a military prison for refusing his order to fight. In his twenties, he roamed across the United States, went to Europe twice, and made one journey around the world. In 1983, he landed in Japan, where he became a professor at a private university and retired as a professor emeritus. He is the author of three novels, a novella, a memoir, and over twenty research papers on teaching. He and his wife live near Fukuoka, Japan. Click here to find out more about Norris.

You can find inspiration in his book, The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don’t Rise, in paperback or Kindle e-book. (Releasing Jan. 17, 2023, available for preorders.)

Read more childhood memories and other contributions from Boomer readers in our From the Reader department.

Have your own childhood memories or other stories you would like to share with our baby boomer audience? View our writers’ guidelines and e-mail our editor at Annie@BoomerMagazine.com with the subject line “‘From Our Readers’ inquiry.”