William Shennan at War

Experiences in World War II and life after war

Canadian writer and community planner shares memories of his father, William Shennan, who served with the Canadian Army during World War II.

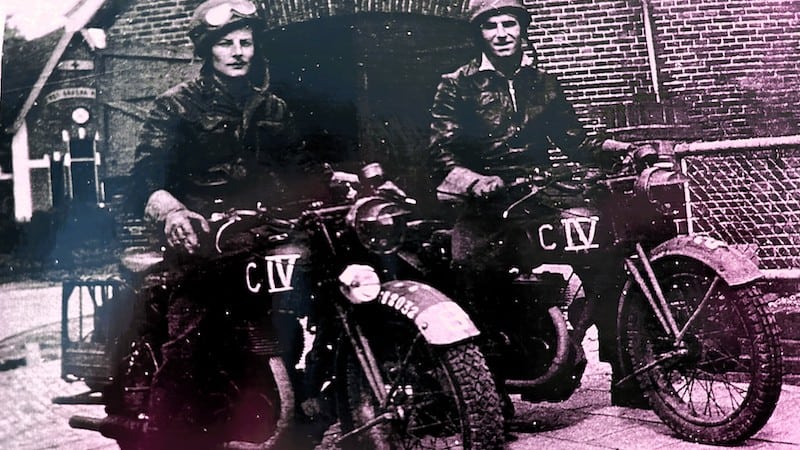

In the photo above is my dad William Shennan on the left, with his buddy Alf Pellant on the right, sitting on their Norton 16H motorcycles. My dad was a dispatch rider for the Canadian Army during WW2, and the picture was taken probably in Belgium, 1944. He stormed Juno Beach, in Normandy, France, June 16, 1944, 10 days after D-Day.

William Shennan was the eldest son of four sisters and two brothers, growing up on a homestead north of Spruce Grove, Alberta, near the Michel Indian Reserve No. 132 (where he met my mom, Christina Callihoo, at a school dance). I remember my dad saying he joined a threshing crew, and they pitched bundles with pitchforks, from horse-drawn wagons into threshing machines, starting in central Alberta and continuing east into Saskatchewan. After the harvest was over, he volunteered for the Canadian Army, his date of attestation: Feb. 4, 1941, as shown in his soldier’s pay book.

I have another picture of Debert, Nova Scotia, where he was stationed before sailing on the HMT Pasteur from Halifax to Gourock, Scotland, Nov. 1 to 13, 1941. He said it was a rough crossing of the North Atlantic, as the ship seemed to be a round-bottomed scow and it never stopped rocking. When he was trying to sleep, he said he had to constantly keep his hands in a protective position so his head wouldn’t hit the steel hull. He came very close to being seasick, but managed to ‘soldier on,’ while many of his new buddies spent most of their time hanging over the taffrail.

The 13th Canadian Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, moved on training missions (and taking prescribed courses) from one location to another throughout Great Britain for the next two and a half years. There are pictures of my dad in Scotland, the birthplace of his parents. He said he stopped visiting relatives after a while as everyone was kissing and hugging him and giving him gifts. I can only imagine how they felt. A shy 20-year-old nephew, suddenly showing up at their front door in his Canadian Army uniform, ready for war. I’d want to hug him, too. There’s also a picture of a young lady, Mae Cameron, with her infant daughter, wee Sandra. I don’t know if she was a relative; my mom says she was one of my dad’s girlfriends.

Besides training and taking courses, he spent a lot of time in British pubs. He said picking fights with American and British soldiers was a pastime. He passed on this gem: an American soldier walked into a pub as if he owned it; a Canadian soldier walked in to a pub as if he didn’t give a damn who owned it.

In 1942, he volunteered for Dieppe but was refused. Given the tragedy of that invasion, I’m happy he didn’t go.

This is where most of the stories stop. He never mentioned storming the beach at Juno, but one of the few things he did say: he quickly learned exactly where a big German mortar would hit and explode. He avoided the direct hits. He was a survivor.

I do have a record of his thoughts written in his very legible cursive style on the back of a personal message given to all troops by Field Marshal B.L. Montgomery. The message was distributed just before they crossed the Rhine River in February 1945. I wonder if my dad wanted to record his feelings for posterity, thinking he may not survive. Writing at 0130, Feb. 8, 1945, he says he was frustrated at being in the same position for four months, but now with the barrage from 1,040 big guns, it seemed as if all hell broke loose on earth. He loved every minute, along with 25 or 30 night searchlights he could see from his station, lighting up enemy positions. He goes on to say it was a long hard day, but he doesn’t mind. At first light they will invade Germany and, as he says: “This thing is going to be finished once and for all.”

On a lighter note, there are pictures of another girlfriend, Bertha, a pretty blonde Belgium girl – and later in his photo album, a picture of her formal wedding (the groom wearing a splendid top hat and tails). My dad learned to speak a little Flemish when he was with Bertha, and she gave him a small St. Christopher medal to wear around his neck for protection. He said he wore it throughout the war – it certainly seems to have been the right talisman. Bertha would write to my dad after he returned to Canada, but my mom put a stop to it, telling her William is now married and it’s time to move on. I often wonder if Bertha’s husband knew of these letters.

He did mention sailing home across the North Atlantic on the RMS Queen Mary, probably in June 1945. He said there were so many troops aboard that they could only eat two meals a day. But he didn’t seem to mind as he was coming home with only a broken ear drum, caused by a German wire strung across a road to cut dispatch riders in half. He probably saw it at the last second. Later, he obtained his medals: 1939-1945 Star; France-Germany Star; Defense Medal; and the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp.

When I was very young, probably 4 or 5, I asked my dad if he ever killed anyone in the war. My mom immediately jumped to my dad’s defense. Her eyes were blazing when she said, “Don’t you ever ask your father that question again.” I never did. But one of the things I liked to do was go through his cardboard box of memorabilia. For a while, it became a kind of macabre obsession for me, as it had swastika shoulder flashes, Maltese cross medals, and pictures of bodies stacked like cord wood at concentration camps. His items were in there, too, including the goggles he is wearing in the picture, and his soldier’s pay books.

I know he suffered ‘shell shock,’ now known as post-traumatic stress disorder. Every once and a while, he would unexpectantly explode at an insignificant issue. He had migraines, too, which he said would start with a stiff hand, pain moving up his arm, and then settling in his head. But he was strong willed, and when he set his mind to something he got it done. I think that’s how he dealt with shell shock. He told me when I was an infant, he used to get up in the middle of the night to have a cigarette to stop coughing. When he realized how senseless it all was, he immediately took his tobacco pouch and papers and threw them in the garbage — never to smoke again. As he got older, he became more mellow and was an avid golfer, preferring the championship courses. He also enjoyed supporting my mom in her music. I called him the roadie, as he was often seen lugging an electric piano or a heavy guitar amplifier to one of her many gigs.

When I was older, probably in my 60s, he and I would talk about death and the best way to go. He often said he’d like to die like his brother Robert, who died in his sleep. Dad came close. On a Thursday night after one of my mom’s many gigs, he said to her, “Let’s have a drink of wine tonight. I know we only have a drink on weekends, but for some reason I feel like having a glass with you tonight.” My mom agreed and later, as she was in the bedroom, she heard a loud crash in the bathroom. William Shennan, courageous soldier, loving and supportive husband, loving father, and grandfather died instantly of cardiac arrest at age 82 in 2003. His ashes are scattered on a championship golf course.

Also from Wesley Shennan: Coral Reefs and Environmental Resilience

Wesley Shennan, a member of the Michel First Nation, Treaty 6, in the area currently known as Alberta, Canada, is a community planner and has been working with First Nations in British Columbia for the past 22 years. His education in both the physical and social sciences, and work experience, has led him to share his understandings and encourage others to take action. He lives with his wife, Elena, in the now smoky and scorching hot Okanagan valley in southern British Columbia – the traditional unceded territory of the Syilx Nations. He is the author of “Indigenous Reconciliation and Environmental Resilience” (FriesenPress, July 24, 2022). “I’m now living in Kelowna and respectfully acknowledge the unceded Traditional Territory of the Syilx (Okanagan) Nations,” Shennan says.

As an Amazon Associate, Boomer Magazine earns from qualifying purchases of linked books and other products.