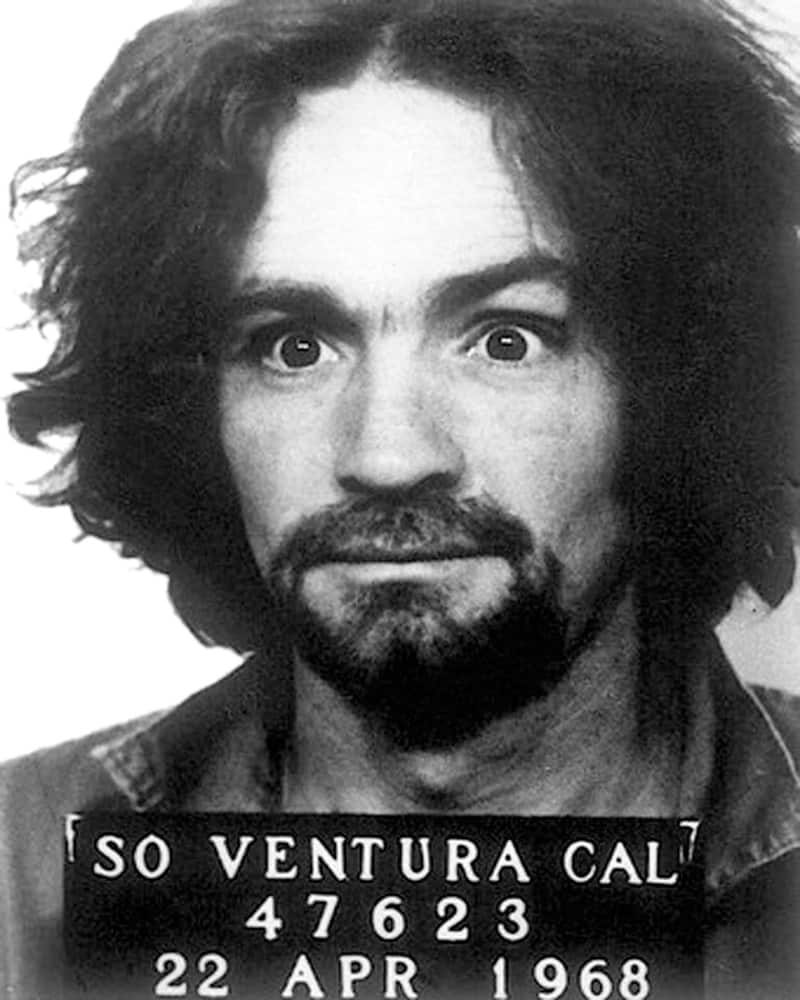

Charles Manson: Hope, Tension, Excitement, Fear, Suspicion

Among the contrasts of our times

That August of 1969, Barb and I were among the privileged few living south of Broad Street in Charleston, South Carolina. When you live in the Holy City, an address “South of Broad” ordinarily means dinner parties on expansive piazzas in pastel homes and midnight sails along Oyster Point in a big sailboat (one with standing headroom).

That August of 1969, Barb and I were among the privileged few living south of Broad Street in Charleston, South Carolina. When you live in the Holy City, an address “South of Broad” ordinarily means dinner parties on expansive piazzas in pastel homes and midnight sails along Oyster Point in a big sailboat (one with standing headroom).

But we were pretenders. We did indeed briefly occupy a mansion on historic Legare Street (pronounced Legree, like Simon), but only for the month and a half the homeowner was traveling in South Africa. Both of us had been newly hired at The College of Charleston to teach English that fall, and we also had stumbled into a housesitting opportunity beyond our wildest dreams.

We arrived at a cobblestone driveway in mid-July, driving carefully as befit the fakers we were, and parked our 1957 red Plymouth Belvedere (the one with high fins and push-button drive) as far toward the back of the lot as we could. We wanted it out of sight of neighbors driving past in an Alfa or Mercedes. Fresh from grad school and new degrees, we looked a lot like hippies, and to some extent we were. My hair was long, and Barb’s was to her waist. We knew the joys of bell-bottoms, boots and beads – and, yes, there was that car.

The country was running on taut nerves in 1969. The year before had seen the massacre at Orangeburg and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. Protests against the Vietnam war were widespread, and the national draft lottery was coming up in December. Kent State was on the horizon.

A FRESH START

But that summer was an auspicious beginning for us. We had been married for eight years, with one or both of us in college every single one of those years. Now we were both “professors,” at the lowest of levels for sure, but in a great town and at such a neat school that we arrived somewhat giddy over our good fortune.

The house, grand and beautiful from the outside, was dark and mysterious inside. The furniture was French, ancient and delicate, nothing you’d really want to sit on or eat at. The living room sofa was a mahogany Empire daybed (Barb said) bearing no resemblance to either a sofa or the daybed your grandma owned. There were side cabinets with marble tops and gilded bronze, a huge buffet – all of it impressive to long-impoverished students.

MOONSTRUCK

In the midst of war and assassination, the country was ready for good news, too, and it came midsummer, on July 20, shortly after our Charleston arrival. Apollo 11 sent out Eagle, its lunar module, and America was on the moon. The moon landing was proclaimed “the television event of the decade,” and if you saw it, you probably remember where you were. We watched it, live and in color, from the comfort of a four-poster bed so tall I needed a running start to get into it.

As we settled in to life in Charleston, we telephoned a friend from Georgia to come see this beautiful city and our amazing unexpected windfall of a house. Ray was a fellow student with whom I had studied for exams – a strange but interesting introvert (another hippie type) who lived so quietly and spartanly in Athens that I knew he’d appreciate our temporary splendor. His response was immediate: Yes, he would come, arriving in two days.

MURDER MOST FOUL

That same day brought more news, news that would soon turn the “Summer of the Moon Landing” into the “Autumn of the Tate Murders.” It’s hard to convey now the impact of and preoccupation with a series of grisly murders that happened way across the country in L.A. the second week in August. Five victims, including actress Sharon Tate (who was 8½ months pregnant), had died in horrifying fashion at the hands of … no one knew.*

A day later, when another L.A. couple, the LaBiancas, were murdered in the same brutal fashion, Charleston, like much of the country, was seized with something unsettling, a quiet sense of mistrust and unease. Fear and rumors spread. Was this unholy craziness the work of some revolutionary group bent on creating revolt and chaos coast to coast? Were those damned hippies responsible? Would there be copy-cat murders across the country, as authorities speculated?

My journal tells me that the afternoon we heard of the murders, Barb and I took a walk down to the Battery, the beautiful park and waterfront area on the tip of the peninsula that is Charleston. On each street corner, it seemed that everyone was discussing the case, and we were struck with the juxtaposition of the impossible beauty of our surroundings and the ugliness of things afoot in the land.

SUSPICIOUS MINDS

There weren’t many hippies in Charleston that summer. Maybe they’d all left town to head up to Woodstock, but as the media shared new details, reporting that the word “Pigs” had been scrawled on the door of the Tate home, the only resident hippies on Legare Street felt – or imagined – stares and whispers as they walked. We, in turn, didn’t like the looks of our neighbor on the right and weren’t too sure of the ones on the left, either.

The mailman had a theory, as did the gardener who showed up unexpectedly to prune the roses and water the plants. What kind of person would do such a thing, why had it happened, who had killed all those innocent people in those beautiful mansions where they no doubt had felt so safe? And, if such horrible things befell the rich and famous, were any of us safe?

By now we were not eager for company. The house seemed a little darker, with too many rooms and nooks to check out for – what? Intruders? Murderers?

It was hard to ignore the creaking and groaning of floorboards during the quiet nights. It sounded much like footsteps in the hall. Sometimes Barb would get out of bed and listen at the door to make sure no one was coming to get us.

Ray arrived, as promised, early on the morning of Aug. 10. He barely got out of his car before he started theorizing about the Tate murders. He knew every gory detail and had obviously studied available information with as much enthusiasm as he had had for researching Paradise Lost. It was all he wanted to talk about, with an almost unhealthy eagerness. The fascinations of Charleston were lost on him. Dinner at a fine restaurant was highlighted with talk of messages in blood and ropes from rafters. Ray was beginning to seem a little creepy.

That night, Barb changed the sheets on a sleigh bed in the room farthest from our own in that sprawling house. When we got to our own room, Barb checked under the bed, locked us in and asked for my help in moving a 6-foot-high chest of drawers against the door. As we whispered in bed about Ray’s excited and almost passionate interest in the sickening details of the now-seven L.A. murders, I heard once again the creaking boards in the hall outside our room, seemed to hear footsteps stop just outside our door, and then silence. Barb and I were immobilized, straining our ears and waiting.

After a long pause, we began to breathe again, and I chanced saying a few reassuring words to Barb. Immediately there was a soft knock on our door.

“Yes?” I timidly responded after a little pause.

“I just wondered,” said Ray’s disembodied voice, “if you’d mind if I moved to another room? I won’t be able to sleep because there’s no lock on my door.”

AS IT TURNS OUT, THOSE WERE THE SAFE TIMES

Forty-six years later, in the summer of 2015, there was this: a mass shooting of a dozen African-American worshippers attending a prayer meeting at a church in downtown Charleston. Ten died. Mass killings and widespread fear mean something entirely different in the United States now.

Unlike the old days of the Tate killings, when details and images crept and leaked out a bit at a time, mass murders now play out live on “Breaking News” TV, with no end of terrible details and generally no doubt of the perpetrator. We get more knowledge more quickly, so we can be more certain that our fears are now more realistic and totally justified. The statistics since 1969 surely prove it.

Sadly, we in 2019 also know there’s no longer anything we can drag against the door.

*Charles Manson and his bizarre, hate-filled philosophy gained a cult following in the late ’60s. In the summer of 1969, he and his “family” brutally murdered at least nine people. On Dec. 8, he and five group members were indicted for the murders. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders was published in 1974, examining Manson’s hold over his followers and the courtroom drama of the trial.

Randy Fitzgerald is the author of Flights of Fancy: Stories, Conversations and Life Travels with a Bemused Columnist and His Whimsical Wife, published in 2017. He was a columnist for The Richmond News Leader and the Richmond Times-Dispatch.