'The Great Mint Julep of the South'

Two slaves, then freemen, known for their culinary and bartending talents

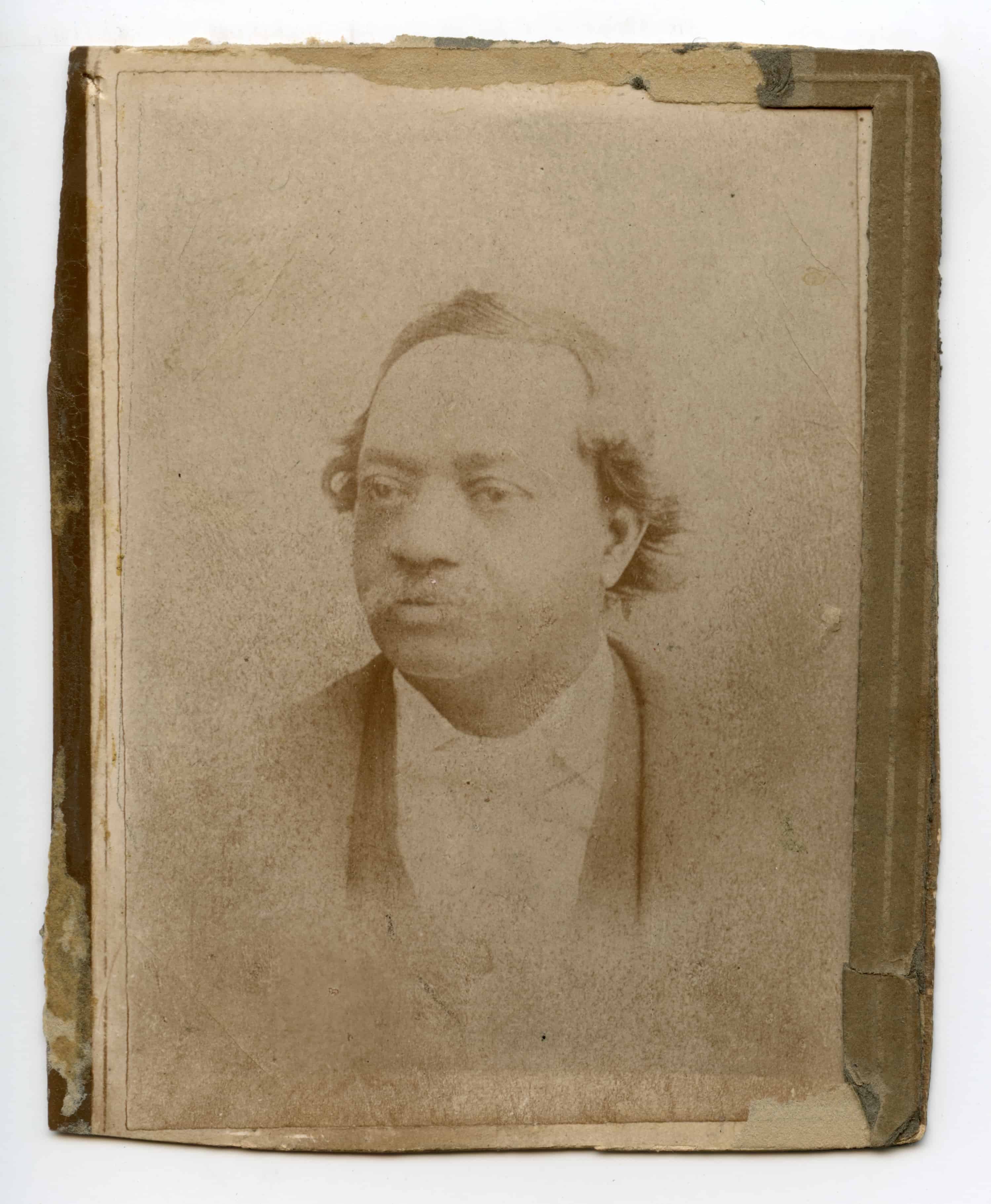

More than a century after Richmonder John Dabney’s death, his reputation lives on. Born a slave in the 1820s, Dabney gained his initial experience as a bartender in a Richmond hotel owned by his owner, Cara Williamson DeJarnette. In the 1850s, Dabney began working on his own, keeping part of his earnings for himself while paying a stipend to his owner.

He and another African-American, Jim Cook, worked at the Ballard House hotel, where they became known for their culinary and bartending skills. In the book Southern Spirits, author Robert F. Moss tells Dabney’s and Cook’s stories as “The Great Julep Makers of the South.”

After explaining that mint juleps historically were big-city-bar drinks – not Southern-plantation-veranda concoctions like we typically envision – Moss says, “Many of the men running the show behind those bars were African-Americans, most of them slaves, and they figured out how to use bartending as a way to earn fame, gain some degree of autonomy, and – in some cases – even achieve their own freedom.”

The mint juleps that Dabney and Cook presented were visual masterpieces. One account describes a giant, multiserving silver cup topped with a one-foot-tall pyramid of ice, ice-encrusted sides and a cornucopia of fruits sticking to the ice in stunning artistic designs.

Edward, Prince of Wales (Queen Victoria’s son, who would become King Edward VII), stopped in Richmond in 1860. “Having heard that ‘Richmond boasts the possession of the best compounder of cooling drinks in the world,’ the prince undertook to try one,” says Moss. Newspaper accounts of the time say that Jim Cook took the mint julep – impressive in appearance and taste – to the prince, who was so impressed he ordered two more before leaving town the next morning.

In 1856, when his wife was to be sold outside of Richmond, Dabney used his earnings and the assistance of influential white acquaintances to purchase her and set her free. He continued to build his reputation as a bartender, caterer and man of integrity.

John Dabney’s Mint Julep

From The New Lucile Cook Book, 1906

Crushed ice, as much as you can pack in, and sugar, mint bruised and put in with the ice, then your good whiskey, and the top surmounted by more mint, a strawberry, a cherry, a slice of pineapple, or, as John expressed it, “any other fixings you like.”

EXPLORING HIS ROOTS

Southern cuisine and African-American heritage

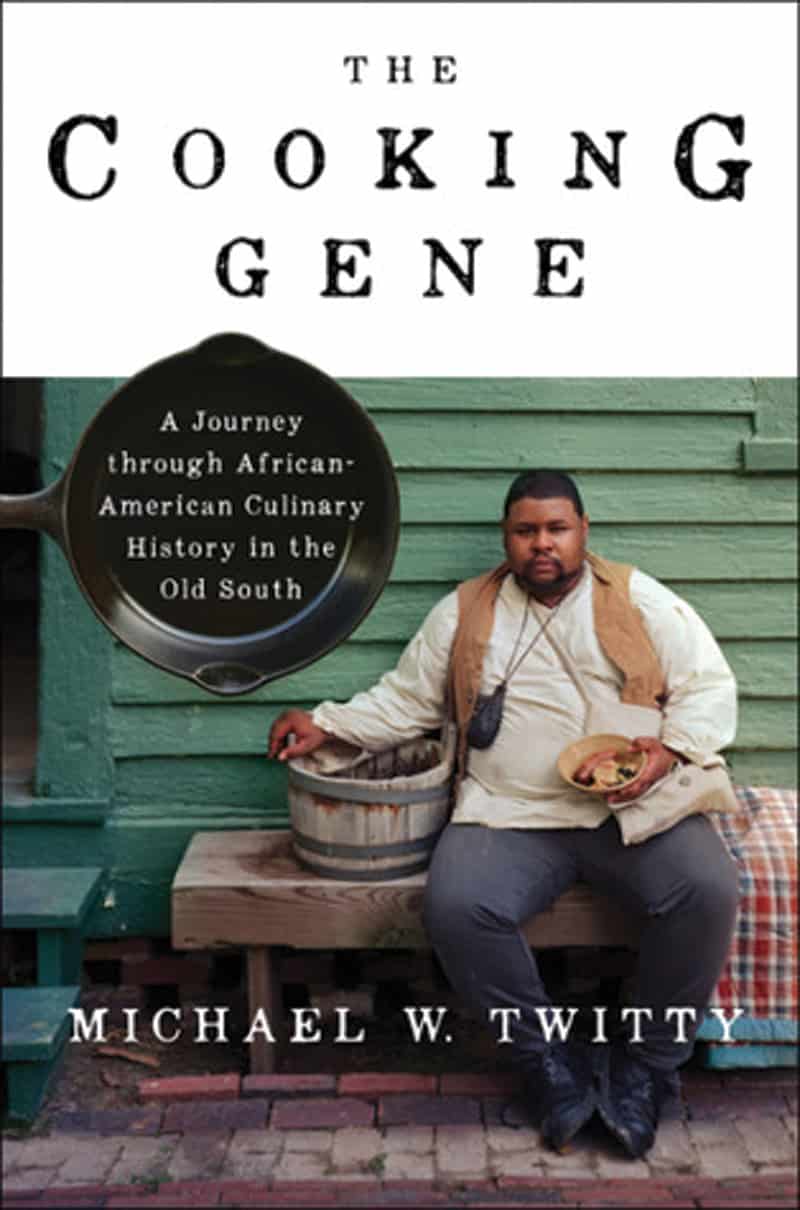

On a search for the roots of Southern food and for his own family background, culinary historian Michael W. Twitty traces the heritage of both from Africa to American, from slavery to freedom. He documents his journeys and discoveries in his memoir, The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South (Amistad HarperCollins, 2017). The book includes a handful of traditional recipes, such as Funeral Potato Salad, Macaroni and Cheese the Way My Mother Made It, Beaten Biscuits, Catfish Stew and African Soul Fried Rice.

Sweet Potato Pie

From The Cooking Gene

2 large boiled sweet potatoes (orange, yellow, or white)

2 tablespoons spiced rum

3-4 eggs

1 cup of sorghum or light molasses

dash of salt

¼ cup freshly churned butter

pinch or two of nutmeg (optional)

1 9” pie shell

Preheat the oven to 375˚. Mix all of the ingredients for the inside together and pour in to fill the crust. Bake for 45-50 minutes or until the knife or fork comes out clean.