‘Reign & Rebellion’ Exhibition

Learn from history at at Jamestown Settlement and Yorktown Victory Center

The theme of “Reign & Rebellion,” a new exhibition divided between two Virginia Tidewater museums, sheds light on America’s early years as it puts today’s political tensions in perspective. Travel writer Martha Steger offers an overview.

“In the beginning, all America was Virginia.” – William Byrd, 1732

History connects us to past times often present in our daily lives. The exhibition “Reign & Rebellion,” at Jamestown Settlement and the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown through Sept. 5, 2023, provides a good example of the 1603-1714 Stuart monarchy’s impact on Virginia – and indirectly on America as a whole.

Our world today echoes the exhibition themes of upheaval, instability, radical politics, and intense religious debate of the 17th and 18th centuries. Videos that are quite modern in look and feel remind us we’re living through our own trying times.

With the approach of the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution (2026), the exploration of England’s Stuart dynasty has never been more relevant. Seventeenth-century colonists brought with them English history, culture, and attitudes that entwined with those of Virginia’s Indigenous population and individuals forcibly brought from Africa.

Virginia’s royal connection

On a lighter, daily-news level, the exhibits are timely. With so much interest in British royalty over the past few years and the death of Queen Elizabeth II in 2022, the exhibit offers a teaching moment on the British Crown, especially for Virginians: James I, former king of Scotland, joined the two long-warring nations and became the first Stuart monarch of England, Scotland, and Ireland, during whose reign Virginia became the first permanent English settlement in the New World in 1607. Decades later, Charles II, king of Scotland, 1649-1651, and king of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1660 until his death in 1685, nicknamed Virginia “my Old Dominion” because of the colony’s loyalty during England’s Civil War, 1642-1651.

Jamestown Settlement covers 17th-century Virginia and the American Revolution Museum at Yorktown covers the 18th century. This gives the two exhibitions distinctly different emphases; but common threads connect the story lines. Largely through benign neglect, the Stuart monarchy laid the foundation for Virginia’s rebellion against England nearly a hundred years after Charles II’s reign: Monarchs had a plate-full of internal problems – a civil war being the great crisis – and gave little attention to Virginia.

Virginians in the meantime learned to act for themselves, without guidance from the mother country. They were shocked when, in 1765, Parliament enacted the Sugar & Stamp Acts on the colonies to help pay off the high debt from England’s war with France. By this time, Virginians had their own distinct identity, resulting in formerly loyal Cavaliers fighting for independence from Great Britain.

The ‘mixed-bag’ of Stuart legacies

While the establishment of slavery in Virginia was a Stuart legacy (slave ownership was legal in England until 1833), other legacies were positive in nature: With England’s having endured a bloody confrontation between Protestants and Catholics, the royal dynasty, according to the exhibition, “established the separation of church and state as well as determined who has rights as citizens, what the function of government is, and the ongoing reckoning with injustice and social and racial inequality.”

Museum panels explain intriguing happenings on both sides of the Atlantic, but the panels do make heavy reading – relieved by an artifacts collection ranging from a unique Indigenous tribal symbol used as a defensive club to a painting of George III’s statue being pulled down in Bowling Green, Virginia, on July 9, 1776. For folks not as interested in a detailed historical refresher, the museums’ videos make the history not only easily digestible but, where appropriate, entertaining.

The videos also make clear that a lot of this history – on both sides of the Atlantic – is extremely unpalatable: Of a Virginia population of 48,000 persons in 1672, two thousand were African slaves, just one-third fewer than the Indian population estimated in 1669.

The monarchy can’t be entirely blamed for the institution of slavery in Virginia: The new colonists governing themselves at Jamestown – the Virginia General Assembly – passed the first law sanctioning lifetime slavery for Africans in 1662, 10 years before James I’s heirs established, in 1672, the Royal African Company to import slaves directly into Virginia from Africa. In 1691, the colony’s General Assembly outlawed interracial marriage – a law that went unchanged in Virginia until 1967.

Curatorial manager Katherine Egner Gruber said, “People are coming to museums for answers about the past, which can help us engage with the present. Museums are safe places to have difficult conversations, and I hope that ‘Reign & Rebellion’ encourages dialog.”

PHOTO CAPTIONS

- James I of England (James VI of Scotland), attributed to Paul van Somer, circa 1618. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, B1982.18. “Reign & Rebellion” at Jamestown Settlement opens with a larger-than-life portrait of James I of England (James VI of Scotland). Believing in his divine right to rule, James insisted that “Kings are not only God’s Lieutenants upon earth … but even by God himself they are called Gods.”

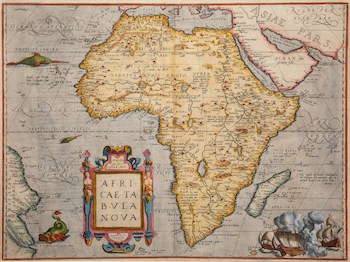

- “Africa Tabula Nova” (New Map of Africa), Abraham Ortelius, The Netherlands, 1570. Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, JS91.38. This map is a result of European exploration and colonization. From the 15th-century Europeans, importantly the Portuguese, were interested in resources along the West Central coast such as gold, ivory, previous gems and, later, human captives.

For special programs related to the exhibitions, visit jyfmuseums.org or call 757-253-4838. The two museums are separated by a 30-minute drive along the scenic Colonial Parkway.

Admission to the special exhibitions is included with general admission to the two museums, $30 for adults and $15 for ages 6-12 with a combination ticket; visitors can also purchase individual museum admissions. Parking is free.

Midlothian-based freelance writer Martha Steger is a Society of American Travel Writers’ Marco Polo member. For 25 years, she was public relations director for the Virginia Tourism Corporation. Of this photo of herself from the archives, she says:

Midlothian-based freelance writer Martha Steger is a Society of American Travel Writers’ Marco Polo member. For 25 years, she was public relations director for the Virginia Tourism Corporation. Of this photo of herself from the archives, she says: