Three Local Books to Promote Awareness of Black Issues

From Reconstruction Virginia to present-day Richmond

You don’t know what you don’t know. Many Americans don’t know much about Black history – or, for White Americans, Black perspective. After all, schools can’t begin to cover all of the information in this vast wide world (and beyond), so they have historically chosen to teach from the majority perspective. Three recent books enrich what we know about local history, supporting awareness of Black issues in Richmond, Hanover County, and Virginia.

Before the Civil War, Richmond was the second largest city in the States for the trafficking of enslaved people. During the war, it became the capital of the Confederacy. As Rev. Benjamin Campbell showed in his 2012 book, “Richmond’s Unhealed History,” the foundation of “racial exploitation, social class, racial discrimination, and heretical religion” began in 1607 and compounded throughout the centuries.

“The cultural assumption of the citizens of metropolitan Richmond of both major races has been that the future can hold hope only if the past is forgotten,” wrote Campbell. “Denial of history, not worship of it, is the anchor that has wrapped its seductive rope around the legs of metropolitan Richmond.”

Three books supporting awareness of Black issues in Virginia

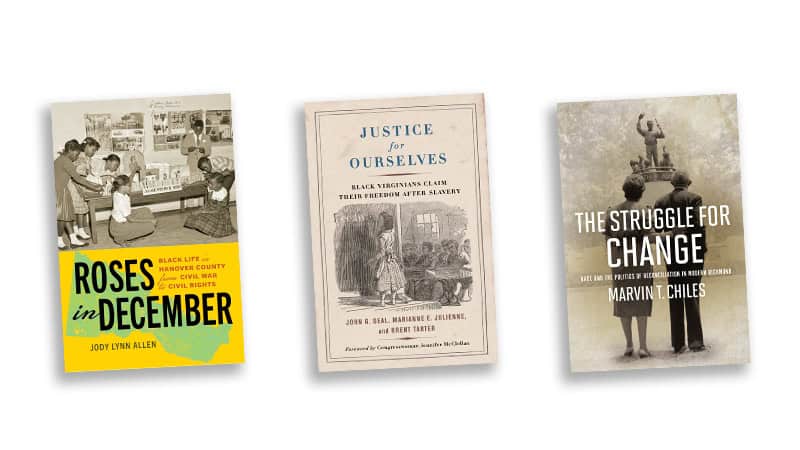

These three books support the awareness of Black issues and local history that Campbell suggests we need. The books cover the efforts of Black Virginians to claim the benefits of freedom after the Civil War; Black life in Hanover County, from the Civil War to the Civil Rights era; and racial politics in Richmond from 1954 to the present.

“Justice for Ourselves: Black Virginians Claim Their Freedom after Slavery”

by John G. Deal, Marianne E. Julienne, and Brent Tarter, editors of the “Dictionary of Virginia Biography” at the Library of Virginia (University of Virginia Press, 2024)

“Justice for Ourselves” traces the difficult journey of formerly enslaved and free Black Virginians in the aftermath of the Civil War. Embracing Frederick Douglass’s insight that legal freedom does not guarantee actual liberation, the book weaves together the stories of teachers, ministers, journalists, entrepreneurs, and political leaders across the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Immediately after the Civil War, Black Virginians sought to define and exercise their freedom by leaving the places of their bondage, reuniting families, establishing schools and mutual aid societies, starting businesses, and entering politics.

The book also shows how white leaders often resisted Black progress. They passed restrictive laws that could be used to incarcerate Blacks – barring canes, public smoking, and vagrancy – and enacted voting restrictions.

Such efforts hampered progress, but Black Virginians responded by contesting oppressive laws, organizing politically, forming fraternal and educational institutions, and advocating for fair labor. Their persistence helped to shape Virginia’s public life and influence politics, schools, and voting rights in Reconstruction

Set before the rise of Jim Crow, the volume shows how freedom’s promise often fell short even then, but also how African Americans strove to claim autonomy with dignity and agency. This narrative re-centers Black voices, illustrates how personal ambition, community organization, and political engagement joined to contest inequality and properly define freedom in Virginia.

“Roses in December: Black Life in Hanover County from Civil War to Civil Rights”

by Jody Lynn Allen, Assistant Professor of History at William & Mary (University of Virginia Press, 2025)

“Roses in December” offers an account of African American life in one rural Virginia county, from emancipation through the Civil Rights era. Centered on Hanover County, just north of Richmond, the book highlights the resilience and achievements of Black residents as they navigated the challenges of Reconstruction, Jim Crow segregation, and resistance to desegregation.

During Reconstruction, Black Americans built strong community institutions. Schools, churches, and businesses reflected their hope and determination to create a better life for themselves and future generations.

In 1902, Virginia adopted a new constitution, designed to disenfranchise African Americans and poor white voters without explicitly violating the 15th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. It weakened local governments, particularly in Black-majority counties, and laid the foundation for Jim Crow segregation in schools, transportation, and public life.

Hanover’s Black residents continued to resist through civic engagement and community-building. Allen emphasizes everyday forms of cultural resistance and enriches the narrative with oral histories that illuminate personal and group strategies for dignity and survival.

In the post-Brown v. Board era, Hanover County’s response to integration included serious consideration of school closures to avoid compliance, mirroring Massive Resistance tactics in other parts of Virginia and the South. Nonetheless, Black families persisted in pushing for educational equity and opportunity.

Allen weaves archival material with local voices to provide a compelling portrait of rural Black life, which is often overlooked in favor of urban-focused civil rights histories. With a balance of scholarly depth and narrative warmth, “Roses in December” reveals how dignity, resistance, and community defined Black life in Hanover County, reflecting the struggles and triumphs of African Americans across the South.

“The Struggle for Change: Race and the Politics of Reconciliation in Modern Richmond”

by Marvin T. Chiles, Assistant Professor of History at Old Dominion University (University of Virginia Press, 2023)

Richmond leaders sought to reconcile and heal racial divisions after the accomplishments of the Civil Rights era, but their efforts often produced unintended consequences, says Chiles in “The Struggle for Change.” The book divides the decades since 1954 as “breaking,” “broken,” and “healing.” He argues that initiatives in urban revitalization, public history, education, and housing reinforced (and in some cases deepened) racial disparities in economic mobility, residential stability, and schooling.

Through a detailed narrative, Chiles examines key figures and events from Henry Marsh (Richmond’s first Black city council member in the 1960s) to Levar Stoney and the showdown over the Confederate monuments. He shows how both grassroots leaders and municipal actors, usually motivated by good intentions, led projects that reshaped the city’s landscape, though often with mixed outcomes.

Central to Chiles’s thesis is the paradox that reconciliation measures often reinforced white dominance by enabling selective investment, attracting gentrification, and sidestepping deeper structural inequities.

“The Struggle for Change” ends with an emphasis on the importance of Richmond public schools. Action needs to come not just from leaders but from residents.

By providing separate and unequal education, the Richmond area confines the children of the less fortunate to the dark carousel of low wage labor, which ensures they will struggle to earn livable incomes and maintain stable housing situations. … The area residents who intentionally abandon RPS and thus confine them to a meager function for poor Blacks, should know that they are, in a twenty-first-century context, in line with the fallen Confederates who would be proud to know that in spite of their surrender on April 9, 1865, the citadel of their racist rebellion still maintains a functional system of racial inequity.

Chiles ends quoting Rev. Benjamin Campbell: “‘If Richmond is truly to become the “Capital of Reconciliation,”’ then human investment and sacrifice on the part of the area populace are desperately needed. … Here where racism started in this country is where it should end.”

Review of another book illuminating awareness of Black issues and history in Richmond:

“The Organ Thieves: Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South” by Chip Jones.

Local awareness: roads of racist intent

“Highways were built through and around Black communities to entrench racial inequality and protect white spaces and privilege,” wrote Deborah Archer, a law professor and civil rights lawyer in her book “Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth About Urban Highways.”

In Richmond, Virginia, that reality can be seen most clearly in Jackson Ward, which was split by the construction of Interstate-95 during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Construction of the highway destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses, displaced Black residents with little compensation, and severed community connections. It marked a turning point in Jackson Ward’s economic and cultural vibrancy. The neighborhood that had been dubbed Black Wall Street was devastated by the loss of properties and institutions as well as the physical division.

Actions in Black neighborhoods across the U.S. had similar negative impacts, including Detroit, New Orleans, and Atlanta. Understanding the impact of the placement of the highway leads to a better awareness of Black issues and history today.

Above is the St. Luke Building as seen from Jackson Ward. The neighborhood where the building is was part of Jackson Ward until construction of the interstate. The St. Luke Building served as national headquarters of the Independent Order of St. Luke, a Black benevolent society founded after the Civil War to provide guidance and financial aid to freed Blacks. Maggie Lena Walker, influential Black businesswoman and activist in the late 19th century, had an office here as a leader of the society. (PHOTO CREDIT: Annie Tobey)