“Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865”

Challenges, accomplishments, inspirations

A new exhibition shines a light on an overlooked chapter of Virginia’s past, bringing it vividly, powerfully, and personally to life. “Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865” at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture honors the resilience and agency of Virginia’s free Black population across nearly two and a half centuries, from the arrival of the first Africans through the end of the Civil War, plus a look at Virginia descendants.

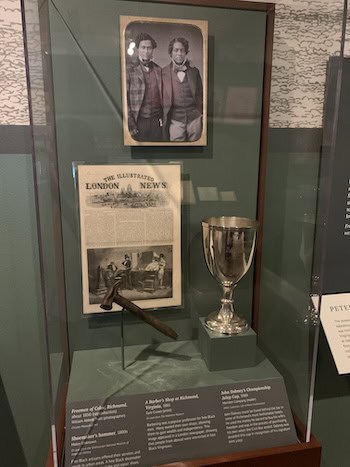

Through rare objects, carefully preserved documents, images, and interpretive panels, the exhibition reveals the stories of people who navigated the complex terrain between slavery and freedom. They were technically free, yet far from equal.

The exhibition’s chronological layout illuminates the shifting status of Blacks in America, from the first Africans arrival in 1619: “As the colony stabilized, a distinct racial hierarchy began to emerge. Virginia, once a society with slaves, was becoming a slave society.”

The exhibition’s chronological layout illuminates the shifting status of Blacks in America, from the first Africans arrival in 1619: “As the colony stabilized, a distinct racial hierarchy began to emerge. Virginia, once a society with slaves, was becoming a slave society.”

The displays also shed light on the motives behind the restrictions – and for the allowances.

The 1705 Slave Code, for example, strengthened the institution of slavery and established legal differences between the treatment of Black and white people: in punishments, court access, and relationships. Throughout that century, Virginia benefited from the transatlantic consumer culture, which relied on the institution of slavery.

On the other hand, Robert Carter III, a member of one of Virginia’s wealthiest families, gradually emancipated the 452 people he enslaved. He was moved by his religious conversion, which convinced him of the immorality of slavery.

Despite the restrictions, free Blacks built communities, pursued education, conducted business, and preserved dignity.

“One thing I’d like people to take away is the magnitude of the accomplishments of free Black Virginians,” says Dr. Elizabeth Klaczynski, associate curator of exhibitions. “They faced many challenges. They faced structures of power that were hostile to them, but they achieved incredible things. They built families, built communities, built wealth – generational wealth. What they did in spite of the obstacles they faced is really powerful.”

The stories are made tangible through extraordinary artifacts, such as:

- The manumission petition of Matthew Ashby, a free man who secured freedom for his enslaved wife and children.

- John Dabney’s silver cup, which he won for his work as a bartender in Richmond and his “Champion Julep.” Dabney saved the money he earned to buy his wife’s freedom.

- A list of students at Williamsburg’s Bray School and a simple set of marbles, reminding us that even playtime held deeper significance in the quest for childhood and education.

- Sarah Jackson’s needlepoint, stitched in Maryland because Virginia barred her from schooling, speaks volumes about Black families’ barriers and their determination.

- A $200 bond signed proudly by Benjamin Short, in full name rather than an “X,” reflecting the pride and self-determination of a man whose freedom was not just a status, but a stance.

The story of the Madden family of Culpeper County offers a striking example of the intergenerational legacy, how free Blacks handed down their determination and accomplishments. Sarah Madden, born free but indentured, rose to success as a seamstress and laundress. Her son, Willis Madden, became a landowner and tavern keeper before the Civil War. He helped establish an enduring legacy through his family’s role as teachers and preachers into the 20th century.

The inspiring “Un/Bound” exhibition resulted from a collaboration with scholars and leaders Tim Sullivan, former president of William & Mary; Jim Dyke, former Virginia secretary of education; and Alvin J. Schexnider, former interim president of Norfolk State University; and institutions of higher education: Norfolk State University, Virginia State University, William & Mary, Longwood University, and Richard Bland College. Their collective expertise ensures this isn’t just a look at the past but a conversation for the present.

“Un/Bound” examines what happened and why. It also celebrates people who persevered and who continues to carry those stories forward. It’s an invitation to see Virginia’s history more clearly and completely and celebrate those who were free, even when the system said otherwise.

“I want people to think about what freedom means,” says Klaczynski. “What does it mean to be free? What is liberty?”

By connecting past and present, the exhibition reminds us that history is not just something we inherit, but something we shape. It encourages today’s audiences to take pride in heritage, advocate for justice, and contribute to a more honest telling of our shared story.

“Un/Bound: Free Black Virginians, 1619–1865”

June 14, 2025 to July 4, 2027

Virginia Museum of History & Culture, Richmond

Learn more: Black History Lessons in Richmond and Virginia