Virginia Suffragists Battled for the Ballot Box

An anniversary of fair representation

A century ago, ask any American woman about the pressing issues of the day, and she might discuss the upheaval from World War I, or the ravages of the Spanish flu epidemic, while others, Prohibition. But a large swath of women focused on one matter above all – having a say in American democracy.

It’s hard to imagine a time when women couldn’t vote, especially since more women than men have voted in every presidential election since 1964. Before the 19th Amendment was ratified on Aug. 18, 1920, women faced blatant discrimination and inhumane punishment for demanding that right.

Until recently, women’s suffrage in America was marginally taught in civics classes, but thanks to a new generation of museum curators, the public is learning riveting stories about the women who fought for female participation in U.S. elections. As the presidential election draws near, let’s look at the hurdles women faced and the outsized role Virginia played in this fight – their stories are being told around commonwealth.

THE BATTLE CRY

The first official mandate for voting rights began in 1848, when a collective of women penned the “Declaration of Sentiments” at a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. Led by Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth and Ida B. Wells, the American suffrage movement was born.

From day one, groups for and against women suffrage agitated along battle lines, and this conflict was especially notable in Virginia. Nearly as soon as the pro-suffrage movement began, the anti-suffragists established their own organizations, explains Christina Vida, curator at The Valentine.

Vida found artifacts and documents written by both pro- and anti-suffragists in the museum’s archives. “They used the media of their time to get their messages out. Letter-writing campaigns, postcards, speeches, rallies – and each platform had a different twist.” From her research, Vida created #BallotBattle, an exhibit that depicts the conflict between Virginia’s suffragists and Richmonders who were outspokenly opposed. Vida used primary sources and reimagined them as social media posts. “We decided to feature five Richmonders of that time period that represented racial and gender diversity,” Vida says.

“Female suffrage was hotly debated,” says Dr. Karen Sherry, curator at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. Sherry developed “Agents of Change: Female Activism in Virginia from Women’s Suffrage to Today,” an exhibit showcasing a century of female activism in the Commonwealth. “Although Virginia’s government voted against the 19th Amendment, the women’s suffrage movement changed the nature of Virginia politics. It ushered in a new era of female civic engagement,” notes Sherry.

A Wave of Revolution

Pro-suffrage forces expanded across Virginia, creating the largest pro-suffrage organization in the South. They believed voting was the cornerstone of a democracy. They wanted their representatives to prioritize issues like public health, education, clean food and water.

The anti-suffragists commenced their own campaign. “The anti-suffrage platform was informed in part by traditional notions of Southern femininity,” Sherry says. “These women were content with their conventional roles in the home. They were satisfied to let their menfolk represent them in politics.”

MARKED BY RACISM

“Agents of Change” also portrays an uglier side of female suffrage. “The suffrage movement was marked by racism on both sides. Many pro-suffrage organizations did not admit Black women or champion racial inequality out of racist beliefs or fear of alienating white support for their cause,” Sherry explains. “And anti-suffrage forces regularly raised the specter of what they called ‘negro domination,’ claiming that giving women the right to vote would empower enough Black women to jeopardize white supremacy.”

In reality, Virginia had revised its state constitution in 1902, issuing a poll tax and an “understanding clause,” similar to a literacy test. These measures successfully disenfranchised nearly 90 percent of Black male voters and 50 percent of poor white male voters and disqualified a majority of women of color, too. Nevertheless, Maggie Walker, the first female Black president of a U.S. bank, was a leading force in the fight for voting rights for Black women; though her efforts were limited by the prevailing racism of her day.

TURNING POINTS

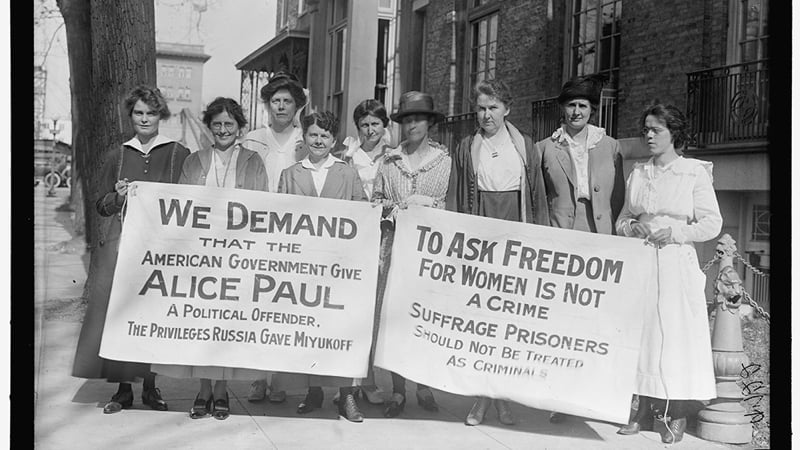

On the national front, Alice Paul, president of the National Women’s Party (NWP), brought 300 of her members to meet with President Woodrow Wilson (also a Virginian) in January 1917. They implored Wilson to support a federal law ensuring women the right to vote. However, he turned them away, declaring it was up to each state to decide.

“NWP solely advocated for a constitutional amendment so suffrage would encompass all women, including those in the South. They wanted uniform voting rights,” says Pat Wirth, executive director of the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial in Occoquan. “The next day, hundreds of Paul’s followers began picketing the White House. They stood there six days a week, Monday through Saturday. Known as the Silent Sentinels, no matter what the weather, there was never a day when they weren’t out holding signs with slogans like ‘Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?’”

Occoquan Workhouse

Six months later, a frustrated president ordered the picketers arrested on charges of obstructing traffic on the sidewalk. These women refused to pay a fine for breaking a law that didn’t exist, and many were transported to the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton. “They gave up their clothing and were served food crawling with maggots, abused and brutalized,” describes Wirth. On Nov. 14, 1917, known as “The Night of Terror,” 32 picketers were arrested and viciously thrown into punishment cells. They were given no food or drink for 36 hours; two nearly died. Lucy Burns, for whom the museum in the Lorton Workhouse is named, was shackled along with her fellow picketers. After starting a hunger-strike, they were force-fed, a recognized form of torture.

When the public learned of the illegal arrests and deplorable conditions, they demanded the president release the suffragists. Worried that rejecting the 19th Amendment was a liability for his party, Wilson transformed his rhetoric and supported the suffragists. The Lucy Burns Museum and Turning Point Suffragist Memorial in Occoquan (under construction), portray the story of those protests.

OVERDUE ELECTORAL EXPANSION

Virginia held out until 1953 as one of nine Southern states that refused to ratify, despite the 19th Amendment becoming the law of the land in 1920. The Equal Suffrage League became the Virginia League of Women Voters; it focused on registering women and paying poll taxes.

Despite national progress, women of color remained largely excluded until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited states from discrimination against racial and language minorities.

We’ve come a long way, baby, but let’s never forget what our foremothers sacrificed to win the keys to democratic participation. Sherry sums it up this way: “It’s often these lesser-known figures that remind us anybody can make a difference by fighting for their cause.”

Virginia Revolutionaries

Lila Meade Valentine – Not only was Valentine a leader in the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, she also persuaded a group of Richmond businessmen to form the Men’s Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. Valentine used her considerable influence to educate Virginia citizens on the issue of women’s voting rights, traveling around the state and holding street meetings in Capitol Square.

Adele Clark – This talented artist promoted the movement by setting up an easel and painting to lure curious bystanders to suffrage speeches. Clark designed postcards, organized rallies; she went on speaking tours to establish new league chapters throughout the state.

Maggie Lena Walker – The African American teacher and banker organized the Richmond Council of Negro Women in 1912. As an activist, she worked for women’s suffrage. She was instrumental in registering African American women to vote.

Coralie Franklin Cook – Founder of the National Association of Colored Women and an ardent suffragist. Cook was the first descendant of a Monticello slave to graduate from college. She was part of the National American Woman Suffrage Association; Cook reminded white women that they could not ignore the political rights of the less fortunate.

Pauline Adams – President of the Norfolk league of the National Woman’s Party. Adams was among the picketers arrested in 1917 and sent to the Occoquan Prison in Lorton. High school teacher Maud Jamison and businesswoman Nell Mercer, both from Norfolk, were also jailed.

Dig deeper into this movement with local museum exhibits.

Dates sourced from The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia by Brent Tartar, Marianne E. Julienne & Barbara C. Batson and from Pat Wirth from the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial